We were excited to learn that recent IBS alum Thomas Calobrisi has co-edited a special issue of The Journal of Dharma Studies, along with his colleague Devin Zuckerman, a PhD candidate at University of Virginia. This month, marketing and communications assistant Gesshin Greenwood chatted with the two about the process of curating and editing an academic journal, histories of science in Buddhism (and why they matter), and the post-colonial agenda in scholarship. We hope this interview will inspire current students to pursue their own academic projects, collaborate, and follow their passions.

Gesshin: Tell me a little bit about how this project came about.

Thomas: The Journal of Dharma Studies is a journal that’s run out of the Graduate Theological Union’s Center for Dharma Studies. It’s a peer reviewed academic journal that focuses on the dharma traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, etc., as well as the contemporary cross-cultural dialogues between them, and the theologies, ethics and culture of them as well. It’s co-edited by Dr. Rita D. Sherma & Dr. Purushottama Bilimoira. I’m the assistant editor for Buddhist Studies there, but really this whole thing is really Devin’s brainchild, so I’ll let her explain more how it came about.

Devin: Right. So I was at AAR in 2017 and I was looking at the catalogue and really interested in history of science, and science and technology studies, and was really surprised to see there weren’t any offerings along the lines of Buddhism and science, beyond topics that we find within Buddhist studies fairly often—like, what is consciousness? What is mind, and how does this interact with our contemporary biomedical paradigm of science? But in terms of histories of science, there wasn’t really anything along those lines. So I was talking to one of my professors and he encouraged me to propose a panel, and so I put something out there looking for collaborators and got in touch with a number of great people, including Thomas. We found out that we both had a lot of enthusiasm and interest in this topic, and so we put together a panel. The panel was wonderful, but wasn’t accepted by AAR [laughs]. We decided later to do something. It was such a good idea that we had to do something with it, so we decided to edit a volume together. So most of the original folks who were going to contribute to the panel ended up contributing to the special issue.

Gesshin: That’s a great example of turning lemons into lemonade. Because now you can say you’ve edited a journal! How did you decide the scope of papers you were going to accept?

Thomas: We were trying to be pretty broad in our approach, and wanted to have a diversity of scholarship from different regions and periods, to show this isn’t just a contemporary issue. We were trying to complicate this vision of how Buddhism and science have interacted since the 19th century, and in particular to look at other types of knowledge formation that have happened in the Buddhist world across time, that have been neglected by our narrow conception of science as dealing with the physical world and using experimental means. We were looking at these broader ideas of what science is as a cultural practice of knowledge production. So it was intentionally quite broad, what we were looking for. We ended up with five papers, and they do express the kind of depth and breadth that we were looking for.

Devin: Yeah it was interesting because on the one hand we did want to have as diverse and broad historical and geographical representation as we could, but on the other hand we were trying to stick to this specific methodological concern, and that ends up excluding the vast majority of what people are thinking about when they’re collocating the idea of Buddhism and science. Usually they [scholars] are not really looking at histories of science and the history of knowledge production in the Buddhist context, which is a slightly more nuanced thing.

Gesshin: I’m confused. Could you explain what you mean by “they’re not looking at the history of science?”

Devin: I think what’s novel about the special issue is that it’s asking for a certain kind approach. Instead of looking at contemplative sciences as an idea, we’re looking specifically at the history of Buddhist knowledge production, so it’s a different kind of methodological approach than what we’ve seen within this conversation of Buddhism and science before.

It’s not necessarily that the current research is all being done within the contemporary context, because there’s certainly people who are looking at premodern texts, but they’re looking at premodern texts in order to understand contemporary biomedical or psychological concerns. For instance there’s a lot of work that’s being done on the ways meditation is described in premodern texts, and how the psychologies that are described within those texts are relevant to how we think about contemporary psychologies and psychodynamic processes and so on. That’s just one example. So we were trying to look at the ways Buddhist cultures and communities have produced knowledge historically, which is a slightly different thing.

Gesshin: That segways well into the next question I was going to ask, which is “Why is the history of science relevant?” Where my brain would go is “It’s relevant because of what it says about contemporary issues,” but it sounds like your goal isn’t just to shed light on current events.

Thomas: Like Devin said, I think a lot of the scholarship going on now is trying to tie premodern psychologies to contemporary ones. What we’re trying to do is break from that mold, by using this broader notion of science in order to try to bring attention to different types of knowledge production that have been set aside, seen as “folklore,” as not really a knowledge discipline by contemporary scholarship. We’re looking for other ways of knowing that haven’t been properly studied by the Western category.

The history of science is a post-colonial effort to break with the triumphalist Western notion of what science is—particularly science as modern, Western, focused on experiments and empirical observations and understandings of the physical universe, within the realm of the “provable.” We were trying to use that critical history to dispel that notion as it informs Buddhist studies today.

Devin: There is a kind of post-colonial agenda embedded in what we’re doing and our efforts to do this. I’m curious now, is the history of science always a post-colonial effort, or is it not a post-colonial effort and only in this modern moment where we start to be able to legitimize other forms of knowledge and bring together other knowledge histories, is that where it becomes a post-colonial activity?

Thomas: There are colonialist or Eurocentric histories of science even from the beginningsbeggings of the Royal Society in Britain in the 17th century, and all throughout. They’re very triumphalist in their tone, especially in the 19th or 20th century, where you get the notion of a scientific revolution. I think the contemporary post-colonial critical history is trying to break from that triumphalist and colonialist mode. So I think not every history of science is post-colonial, or aimed at bringing in broader notions of science. They’re quite narrow.

Devin: There’s also a way in which histories of science as a discipline is evolving to include knowledge and knowledge practices of communities and cultures that lie outside of the scientific method, and there hasn’t been a Buddhist contribution to that yet. So the special issue was attempting to bring together as many folks who were interested in this as possible, so that not only could we make a contribution to Buddhism but there was also a collection of essays that was making a contribution to this new movement within the history of science.

Gesshin: Could you speak more about what you mean by post-colonial agenda?

Devin: That’s a big question for me and my research, but for the purposes of this special issue I’ll just say that when you do histories of science but you’re looking at how knowledge has been produced historically in ways that lie outside of scientific knowledge, outside of the European, triumphalist sense of what is legitimate knowledge, I think that is a kind of post-colonial activity. There’s a lot of questionsquestion for me about the institutions where Thomas and I are producing knowledge and how post-colonial it could possibly be within the Western academy, but those are my thoughts.

Thomas: I’ll just add that a post-colonial agenda means to de-center European discourses of modernity and science, to try to uncover what those European histories and what a Western perspective is occluding or overriding, to bring that into view. So that’s what a Buddhist history of science is doing—trying to de-center that European, white perspective, and trying to take a broader approach to what science is. Then science ends up looking more like a cultural practice that’s historically contingent. What counts as “evidence” in the natural world is always changing.

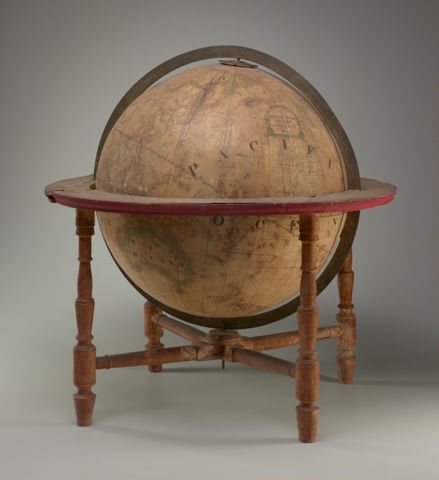

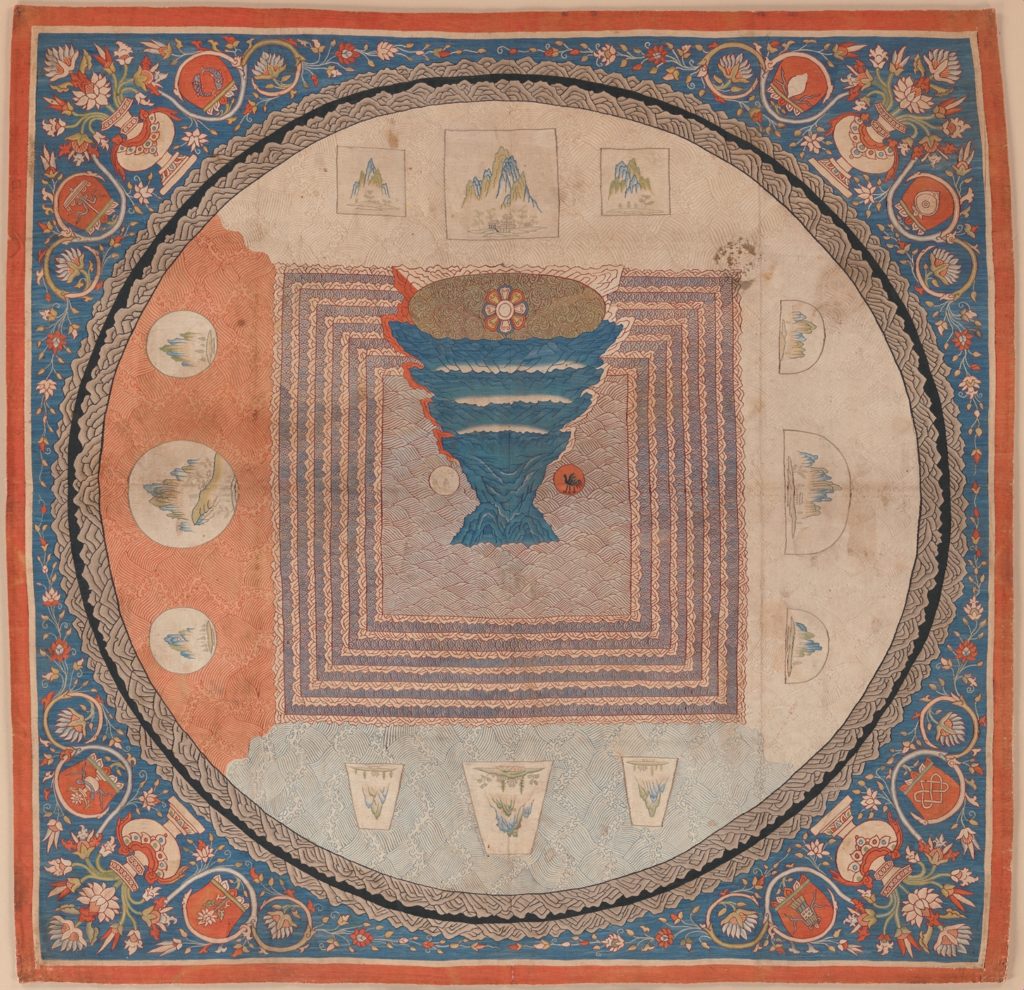

For example, one of the articles in the special issue is “The Offerings of Mount Meru: Contexts of Buddhist Cosmology in the History of Science in Tibet,” by Michael Sheehy. His ending argument is that we can’t understand the Mount Meru cosmology as a kind of physical map of the universe. Rather, it’s integral to Tibetan practice as a cultural understanding of cosmology. So he’s arguing that you can’t replacing it with a spherical earth ritual or something like that.

Devin: What’s really exciting about that article is the history of knowledge interactions, and this history of knowledge that we haven’t seen yet, and the complexities that attend the cultural production of knowledge.

Gesshin: This isn’t Buddhist or academic at all, but it makes me think of astrology and witchcraft and how they function outside of mainstream religion. The critique of them is often that they’re not real. I watch a lot of TikTok; there’s a lot of witches on TikTok, who make things levitate and stuff like that, and there’s this one guy who’s whole schtick is debunking the magic of witches, like, showing how it’s not real and just an illusion. But the optics are weird to me though, because mostly the witches are women. He’s a white man “debunking” all of these young women who are thriving spiritually outside of mainstream religious institutions. It’s complicated because on the one hand, he’s right, the magic isn’t “real,” but it sort of seems like just another way that patriarchal forms of science come in to squash more marginalized ways of knowing.

Devin: It’s a really interesting thing, isn’t it? I think it’s really interesting that there’s suddenly this renewed interest in the occult. There’s a whole Instagram and TikTok culture of witchcraft. What’s up with that?

Gesshin: You should do a special issue on TikTok witchcraft [laughter].

Thomas: That’ll be our next one [laughter].

Gesshin: I’ll look forward to it. Do you have anything you’d like to add about this process of putting together a special issue?

Devin: Working with Thomas—I don’t want to embarrass Thomas, but he’s a wonderful collaborator. The collaborative piece of this has been so exciting and special. I would hope that folks who are reading this and are thinking about directions for their work will look into collaborating with colleagues. Collaboration is wonderful, and there’s too little of it happening in our discipline.

Gesshin: That reminds me of your post-colonial agenda as well. There’s something about collaboration that is very much against the grain of mainstream, patriarchal academia that sort of perpetuates this myth of the “lone genius.”

Thomas: Yeah I remember Devin and I putting together a whole calendar for this—is it Dogen who said “Planning is not the way?” In any event, apocryphal Dogen said something like that. The pandemic did have a big effect [on this special issue]. A lot of people were struggling to attend to family and to their work, and so a lot of things got bogged down. But we had a really wonderful editorial manager, Laura Dunn, who was patient with us.

If there’s anything I want to say to someone who’s thinking about doing this kind of thing is, “You can plan all you want, but really you’re in the hands of other people, so patience is key, understanding is key, and collaboration is a wonderful thing.”

Dr. Thomas Calobrisi is a member of the Adjunct Faculty at the Institute of Buddhist Studies, an assistant editor forthe Journal of Dharma Studies, and book reviews editor for Pacific World: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies. His research focuses on the recontextualization of Buddhist ideas, practices, and artifacts in the American cultural and religious landscape from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

Devin Zuckerman is a doctoral candidate at the University of Virginia. Her dissertation explores theories of the elemental (earth, water, fire, wind and space) within philosophies, cosmologies and contemplative practices in 11th-12th century Tibetan Buddhism.